Digital Venice

Over the past 20 years, an ever-expanding area of Venice has spent an increasing number of days per year submerged beneath the waves. Eventually, the local government had to implement drastic measures, with the help of the UN. For decades, the effects of climate change were predicted accurately and in detail by scientists, but played down by politicians and the private sector. The result of this inaction has so far been reflected most visibly in increased flooding and extreme weather catastrophes around the globe. While robust measures are now in place across Europe, it is unclear whether these will be sufficient. Lifestyles have changed for everyone.

Context:

In a radical move, governments imposed punitive taxes on CO2 emissions through- out the EU, and banned CO2 -producing technology.

Tourism, once a common activity for Europeans and a major source of revenue for many cities, has largely disappeared, replaced by digital travel.

Through virtual reality, most individuals can visit digital real-time replicas of an increasing number of cities around the world.

New forms of digital economy have emerged, all clustered around this new digital tourism.

Mark is 25. He grew up in Herräng, a coastal village near Stockholm, surrounded by the natural beauty so distinctive to Sweden. During the summer, he enjoys hiking and sea swimming. However, the Scandinavian winter is long, and the hours of daylight all too short. In his teenage years, when Mark was too young to go out to the city on his own, he spent the long dark evenings alone at home, playing virtual reality (VR) games remotely with his friends. Mark had always dreamt of big city life and traveling to farflung places. After leaving school, he moved to London, where he spent a couple of years working as a lighting technician in a small theater. In his free time, like most of his generation, he would travel and learn about the history of Europe and the world. Of course, he also had his fair share of fun, enjoying the local nightlife and savoring the feeling of freedom his life- style brought him.

However, 12 years ago, Mark’s long- distance lifestyle came to an abrupt halt. In 2028, new carbon-neutral regulations saw the cost of air travel skyrocket, almost overnight. Mark tried switching to driving, but it was a short-term fix at best. He was forced to sell his car cheaply for scrap, because it was fuel-based and hence banned under the new legislation. Even train tickets became absurdly expensive, as demand spilled over from other means of transport that were now unviable or unaffordable.

The bottom line is that physical travel, especially over longer distances, is out of reach for Mark – and almost everyone else. Plane and ship manufacturers are investing millions in research and development for hydrogen and artificial fuel solutions, and actual products will be launched in the market by 2041. However, policy makers took their radical action long before that – surprising those observers who thought they would always take the safe, soft option in the interests of economic and political stability.

One of Mark’s top travel destinations was Venice. Italy’s “floating city” had suffered from flooding for more than a century, and it had got steadily worse every year. For example, in the early 1900s, the famous Saint Marcus Square would be flooded for around four days a year. By the early 2000s, this had increased to about 40 days a year. Rising sea levels were partly to blame, but the real villains were the deadly storm surges, which were pushing much further inland than ever before, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. Experts from the ENEA (the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development) had been looking at flooding for decades, and had predicted that the Mediterranean would rise by up to 140cm by 2100, swamping 285 kilometers of coastline in the northern Adriatic, including stretches of the Italian coast. In 2030, it became clear that their predictions had been optimistic. Had it not been for drastic measures, and an outpouring of resources from the UN and other organizations around the world, Venice would have been lost to the ocean by 2035.

Although most of Venice was saved as an island surrounded by flooded plains, it has been fully evacuated but for engineers and technicians, who work around the clock to secure it and its treasures. For now, a limited and tightly controlled fleet of drones is the only window on Venice for the rest of the world.

Areas that were less well known, or less historically vital, were not so lucky. By 2100, more than 3,000km2 of coastal plains bordering the northern Adriatic will be flooded, including 33 areas of Italy. This continuous loss impacted the environment, local infrastructures and around eight million local inhabitants, prompting a huge wave of internal displacement within Italy.

Meanwhile, similar disasters were be- falling northern European cities such as London, Amsterdam and Hamburg, which all suffered major damage, disruption and loss of life as their rivers burst their banks, flooding busy urban areas. Along with the catastrophe known around the world as the “Flooding of Venice”, these events finally pushed European governments into immediate and decisive action against climate change.

Taxes on CO2 emissions were increased heavily, and soon afterwards, all carbon- positive technologies were banned. However, electric transport had yet to be widely adopted. One of the hardest-hit industries is transport and tourism: for most citizens, long-distance travel through Europe is no longer affordable. With travel now a luxury, everyone – rich and poor alike – has had to make some major compromises. The European tourism sector, which accounted for over half the global industry, has suffered significantly over the past few years. Visitors to Venice, who had numbered 20m in 2020, declined sharply. Other popular destinations such as Paris, Amsterdam, Rome and London saw a big rise in unemployment, and a new type of poverty arising from the eroding tourist sector.

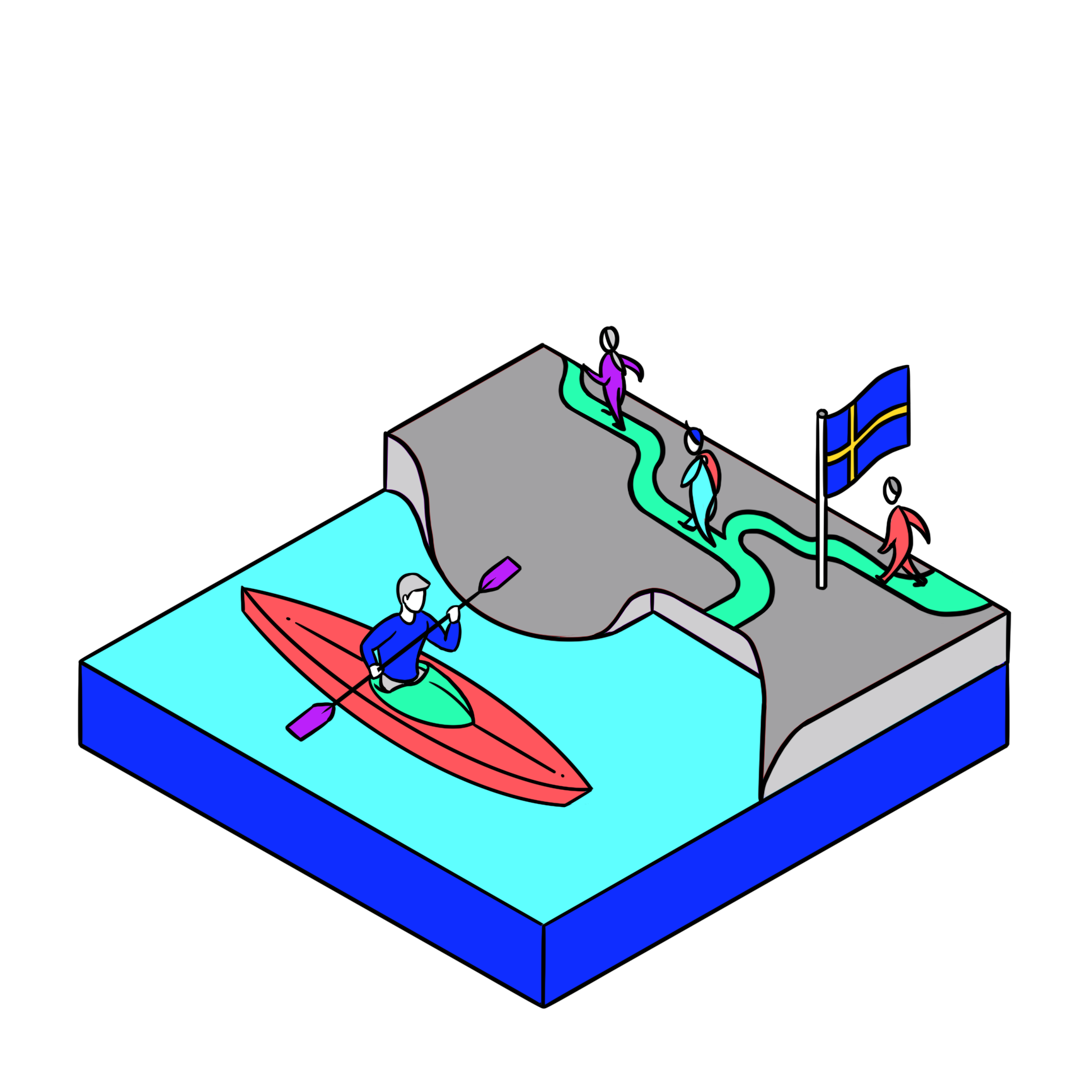

As an alternative to traveling, Mark has started to fill his evenings with VR games again, just as he did as a teenager. His girl- friend Agnes, who previously shared his passion for traveling, can’t understand this hobby, and has even begun to question their relationship. However, they both still enjoy travelling locally, so they go for weekend hikes or kayaking in the nearby rivers, or head to friends’ houses to play board games. While Mark and Agnes see themselves as environmentally conscious, they now realize how much of their free time, and even their short-term life goals, previously revolved around carbon-based technology. Life was what happened in between trips: starting a new semester, or returning to work after a vacation, was made more bearable by the thought of the next journey. Now, the globe- trotting generation who started with InterRail and graduated to EasyJet are grounded – apparently for good.

But what if there was an alternative to physical travel? Over the past 20 years, technologies such as artificial intelligence, smart sensors and batteries have all developed rapidly, allowing new designs of autonomous drones that can operate continuously. Originally used in military and surveillance applications, drones now represent a lifeline for the tourism industry.

In the beginning, autonomous drones could fly anywhere, anytime. However, they were soon restricted by regulations. Legislation also aimed to reduce the environmental impact of drones’ significant processing power and energy consumption, as well as addressing safety concerns, noise and visual pollution. Now, as the reliability and safety of drones becomes clear, regulation is allowing the technology to thrive.

The tourism sector, desperately seeking a means of survival, started experimenting with new ideas. High unemployment sparked creative thinking, and cities supported new tourism ideas much as others had supported startups in the past. One of the more successful concepts was to make a digital real-time replica of a tourist destination that could provide tourists with an immersive VR experience. Through these “virtual visits”, people from anywhere in the world could pay a modest fee to “visit” a city remotely without leaving their homes.

Over time, cities have developed their own add-ons to adapt or extend the virtual visit experience. Virtual avatars, powered by artificial intelligence, guide “visitors” through the digital city, adjust the tour to personal preferences and respond to tourists’ requests, actions and preferences. Some avatars are simply styled as citizens of the host city, while others are recreated historical figures, actors, or fictional characters from the local area. These characters bring a much-needed human touch to the visit, turning it from a passive, cinematic flythrough into an interactive, conversational experience. Other cities have added group travel, so couples and families can all “travel” together.

In some ways, digital tourism is even better than the real thing. Instead of browsing a website or a guidebook, you can take a five-minute “taster” trip to see if you like the destination. There’s no queuing, and you can always find a bathroom, or a taxi. You don’t have to learn the local language unless you want to, since tours and can be provided in the traveler’s own native tongue – as can local signage and newspapers. You can “travel” to your destination instantly, stay for as long as you want and split your “vacation” over multiple evenings at home. The only downside is that if you want to try the local food, you have to cook it yourself!

Once Venice had been stabilized, autonomous drones began generating the digital recreation by scanning and replicating the city in real time. They worked independently of any other repair or maintenance work, were unaffected by weather conditions, and had no impact on other drones, devices or people on the ground.

The new mode of “travel” created new opportunities for cities throughout Europe, and began to compensate for the decline in physical tourism. In the case of Venice, it makes a valuable contribution to the costs of restoration too. Digital tourism has also created completely new types of work. Remote workers can act as guides for city tours or museum visits, or provide tuition in how to make local dishes or try out local crafts. New digital experiences are being created every day, and Europe is once again accessible to all – in digital form, at least.

Businesses have sprung up offering to complement the virtual tour with tangible and sensual elements, creating a virtual/ physical hybrid. SensTrav replicates selected areas of major European cities physically, so that people can interact with physical objects during their virtual travels. With this service, Mark and Agnes can open the door to Saint Mark’s Basilica while looking at it through VR glasses, then sit down to enjoy an Italian ice cream.

Now Mark and Agnes can travel together even further, and more often. They don’t need to dedicate a full week to visiting a city – for example, they can pop over to the Louvre on a weekday evening after work. VR, Mark’s youthful hobby, has become a source of entertainment, sharing and learning for everyone. Even though Agnes is still planning a real-world long-distance trip to Colombia in about four years, she’s getting into virtual travel in the meantime. It’s something really different. She loves it!

Since Mark knows European history pretty well, and wants to learn more, he starts working part-time as a tour guide. He still spends his mornings as a lighting technician, then in the evenings he develops pre-programmed tours of Stockholm, his home city, or Venice. Tourists who want an interactive and personalized tour can make an appointment for him to join them and chat as they make their way around the virtual city.

The Sinking of Venice changed the lives of Mark and many other travelers forever. But today, digital tourism has brought new, more positive changes. Mark now gets to visit many more cities than he did before. However, his traveling time is zero, so he can get to know several cities per week without harming the environment. Travel is not just affordable again, but even profit- able, as Mark now makes part of his living from it, so it’s improved his quality of life. From time to time, he can even enjoy a real-life travel experience – just not as often as before.

Opinions:

“The idea of virtual substitutes for mobility is one that is certainly overplayed, and has been overplayed for the last 40 years. People will not stay still because of the climate; it is the other way around. Because of the climate, people will start moving around faster and faster.”

– Nikolaos Kastrinos, Policy Officer at European Commission

“Taxation – there are two flaws with that. One is that even with all the flooding,if a government sees major potential job losses and industrial decline, I don’t think they are going to impose CO2 taxes as astronomical as you describe. And the other thing is, how much of the CO2 is actually coming from personal travel?”

– Anja Schulze, Professor at University of Zurich

“I would like to interact with the people I meet, not only with the ones I already know. And the feeling of sharing my emotions with ‘people’ who aren’t really people scares me.”

– Anna Menasce, Student